On Art, Life, and Cricket’s Answers to Both

Trent Parke and Narelle Autio’s film seeks to distill the essence, and capture the magic, of the sport of cricket

In this essay, Felix White, author of It’s Always Summer Somewhere: A Matter of Life and Cricket, reflects on The Summation of Force, a film by Trent Parke and Narelle Autio. View the trailer of the film above, see a video of it in installation form, below, and at the bottom of the page: watch a new behind-the-scenes video exploring the making of the project.

Trent Parke’s mother died when he was thirteen. Suddenly a young boy loaded with a dangerous dose of mortal perspective, it caused him to interrogate everything. A slew of frustratingly unanswerable questions begun to enter his conscience before being spat back out into a vacuum of endless time. Why was he here? What happens next? What’s the purpose to any of this? They were not so much answered, but becalmed, by the cricket he found on the television: the length of time the game took and the endless detail within serving as a crutch to support this new fixation. “I began to develop this need to know how everything worked”, he says in Art of the Game, a documentary about the making of The Summation of Force, directed by Matthew Bate of Closer Productions. Parke wonders, “How could fast bowlers bowl as fast as they could? How did spinners spin the ball?”.

He began to video-tape every single ball of five-day Test matches, rewinding the tape repeatedly to analyze them. “I would slow it down to see every minute detail of the bowler and what made him be able to bowl that type of delivery, over and over again,” he says. He pauses, as if the next admission might reveal too much about his obsession: “… for years”. Simultaneous to the timely dive into the distraction that cricket afforded him, he found his mother’s camera and, as if it was “the natural thing to do”, began to take photographs with it. “If I took a photo of something,” he considers in hindsight, “I could make sure nothing would disappear.”

Just under a decade later, on the other side of Australia, Narelle Autio had left college and found work experience at the Adelaide Advertiser as a photographer. With a passion for the artform but unsure as yet of her direction, she found herself spending days in the paper’s dark room processing photos from vague assignments. She watched her latest develop: a tight image of the face of a clown, wig not yet fixed, slightly wild eyes looking just off the camera. She threw it away. Ever the perfectionist, she hadn’t quite got the print right. Later that evening, the picture editor saw the image by chance – still face up in the refuse – in a last call sweep of the studio, and salvaged it. It was an enigmatic image of a clown caught between pantomime and frenzy, somehow surreal; a moment unmistakably captured. The newspaper ran with it on the front cover. From there, her career began. “Chance and coincidence”, she reflects, “is an important part of the process in photography.” Some years later still, when Parke had made an overnight decision – after some genuine on field cricketing promise – to pursue photography instead at The Australian newspaper, he looked up from the light-box at his new workplace. Narelle Autio, stationed opposite, by chance and coincidence, looked up from hers too, straight back at him. And that was it.

—

Summation of Force is an astounding moving image installation initially launched to wide acclaim in Adelaide in 2017. The accompanying virtual reality film was selected to premier internationally at the Sundance Film Festival before travelling worldwide throughout 2018. Blending and bending the world of sports and arts into space neither usually occupy, the film opens with the birth of Trent Parke and Narelle Autio’s second child, Dash. In the custom of capturing everything, Dash is recorded the very second he enters the world by Parke, screaming out amid gasps reserved only for the birth of a newborn, before we meet him barely minutes acquainted with his new world, eyes shut then squinting, as the doctor comments on his impressively present light hair. Though Summation of Force does not use the footage, when Dash meets his older brother Jem for the first time – another moment preciously documented – Jem looks upon him from a slight distance as Dash is told, “You’re a bowler, Jem is a batter.”

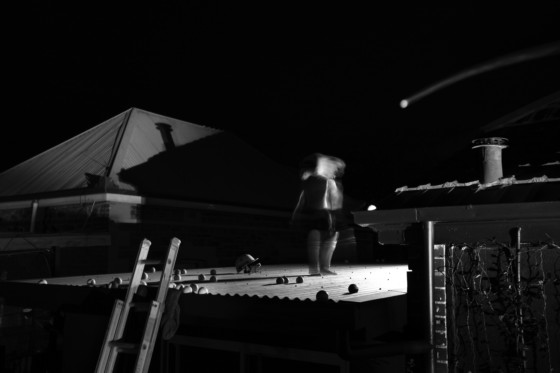

And so it proved to be. In a prologue of sorts to the film’s stylistic introduction, there are flashes of the brothers growing in their back garden; Dash bowling and Jem batting. They wrestle over a bat. They throw and hit the ball to each other. With each frame, they have developed slightly, fractionally bigger and more attuned as cricketers, until they are suddenly carved into their own idiosyncratic techniques. Dash, in particular, his light hair remarked upon by the doctor as now long and thin and wild, approaches the crease in a miraculously precise, cartoonish image of Australian fast bowlers from years gone by. By the time the section reaches its conclusion, he is running in full speed towards his awaiting brother in his back garden. Through the omnipresent sprinkler that somehow serves to frame the way, his body falls away to propel himself further. He leaps skyward – affording an impossible second to pedal himself once through the air itself – and then into his delivery stride. It’s a genuine fast bowler’s action, if somehow completely his own. Parke reflects these formative back-garden cricketing years: “Jem just asked us, ‘How come Dash can bowl fast’?”. It was all the parents needed to ask. A family project that would sprawl out into years had just begun.

“We’re always looking for surreal in the everyday”, Autio says, “Our work is taking the ordinary things that might be happening around us and showing them in a way that might not have been seen before.” The everyday, twenty years into their respective photography careers of international repute, just happened to be deeply cricket-centric. “Our life, especially then,” says Parke, “was cricket.” He reels off the activities: “Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday off, Friday a game, all weekend then all over again”. And so, with Jem’s question on Dash’s technique a resonant starting point into analyzing a process, they looked to do what they had always done; find something about their everyday, ask themselves a question about it, and communicate what they had found with the world outside.

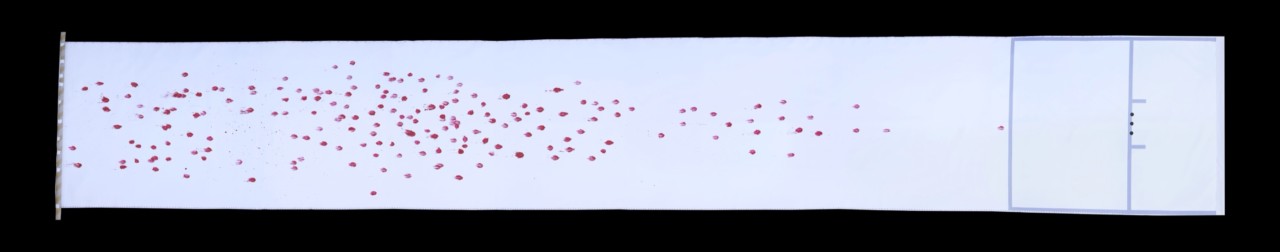

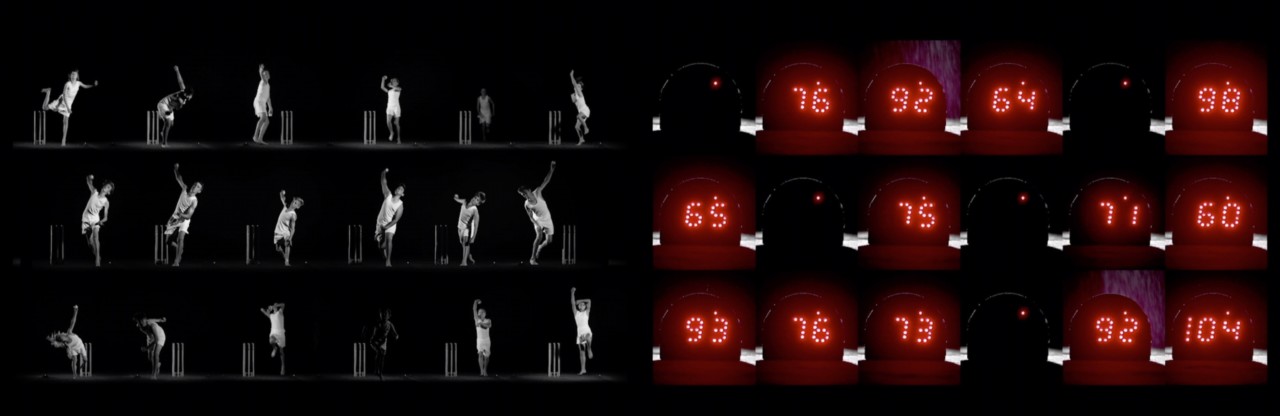

Communicating cricket to the world outside cricket is a hard sell. No other sport talks about itself to itself more than cricket. No other sport is more aware of its traditions, or its responsibilities, or its failings, than cricket. No other sport is more bound to its sights and sounds, preconceptions and routines than cricket. Therein lies the real ingenuity of The Summation of Force. It is a rare document of cricket, with the cricket itself taken away. “The first decision of the film was easy. It had to be shot in black and white to remove everything that we know about the game. We wanted to break it down to light, lines and movement,” says Parke. The parents set up the backyard with a ‘proper cricket pitch’, and started filming their boys, repeating their techniques to their more captive than ever audience. The framework of the film – every frame a photograph come to life – leans on how, when disassociated from the competition, the functional aspects of the game are, without much imagination required, like dancing, or tend to even feel, without exaggeration needed, art. Separated from the usual context, Autio explains, they began to think of the techniques they captured as “really beautiful.” She continues, “It’s not about hitting the wicket at all, it’s about seeing them move.” For the cricket lover, this is where the eureka moment of The Summation of Force lies. It is like finally having a physical document, a tangible explanation for the inexpressible quality of what makes cricket, on occasion, suggest itself thrillingly as something more than just competition.

And for the non-cricket lover, it turns out, it was an opportunity to re-frame the game without the bucket list of reasons not to engage. “I have noticed over time the most arts people generally don’t have a great love of sport,” Parke says, while acknowledging there are obvious exceptions. “A few weeks ago, as we walked into Autio’s new exhibition, an older gentleman came up to me and said ‘I saw your cricket film.” It took Parke by surprise as it has been a few years since it was shown. “I don’t like sport”, the man continued, “but I found myself strangely drawn to your cricket film. It triggered something I can’t quite explain.” Parke found himself “bamboozled” by the conversation, but after digesting it, realized that it “was probably the best reaction we could have hoped for.” The facilitation of this coming-together of two tribes worked the other way too, Autio continues, “The film engaged a lot of ‘non-arty’ people. People who may not have felt they belonged in a gallery found an entry point into a world they thought didn’t relate to them. I loved that part of the film. It embraced a new audience. You are inviting others into your space, a place others may or may not have experienced until you pointed a camera at it. It is almost always about saving things for others to see.”

Though the two tribes may not ascertain it literally, when presented like as they are in The Summation of Force, the affinities between sport and art have never felt closer. Work and play. Instinct and repetition. Evolution and tradition. The individual and the group. Success and failure. Chance, of course, and coincidence. There are breathless moments occasionally, as a sports fan, where you find yourself desperate to pause the film and explain ‘Cricket-is-art-and-I-told-you-so’ at anyone who will care to listen.

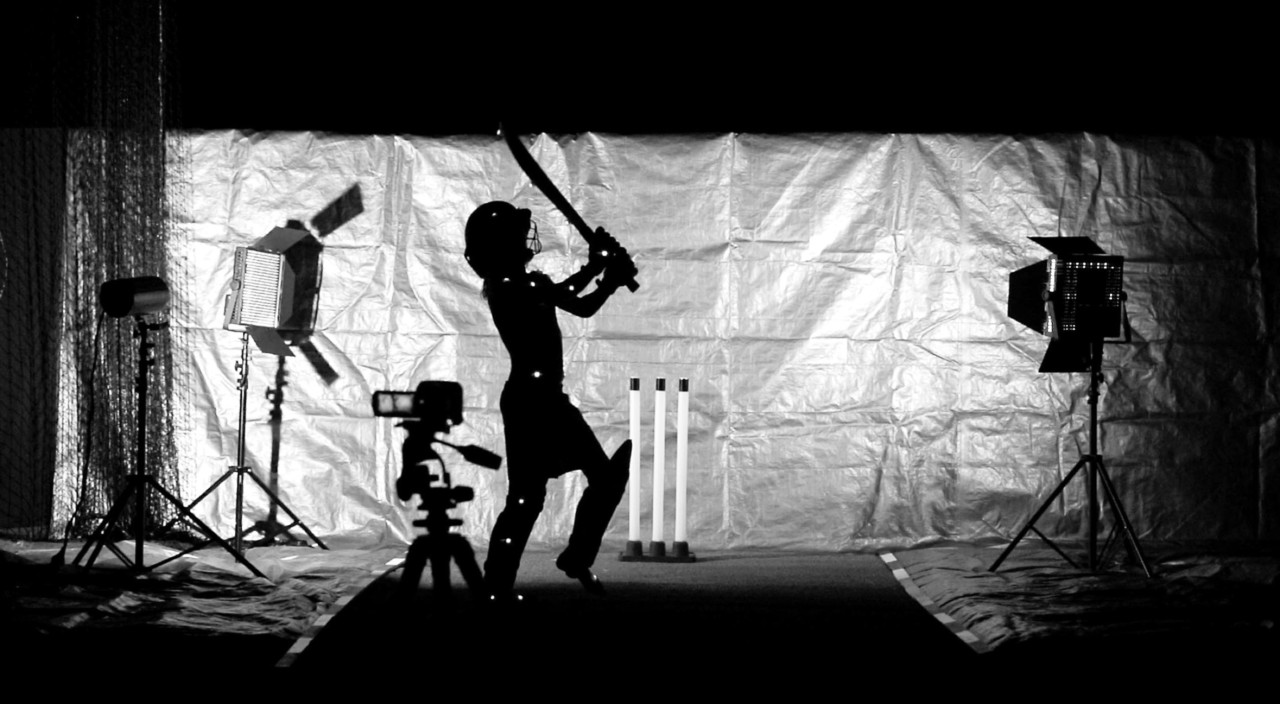

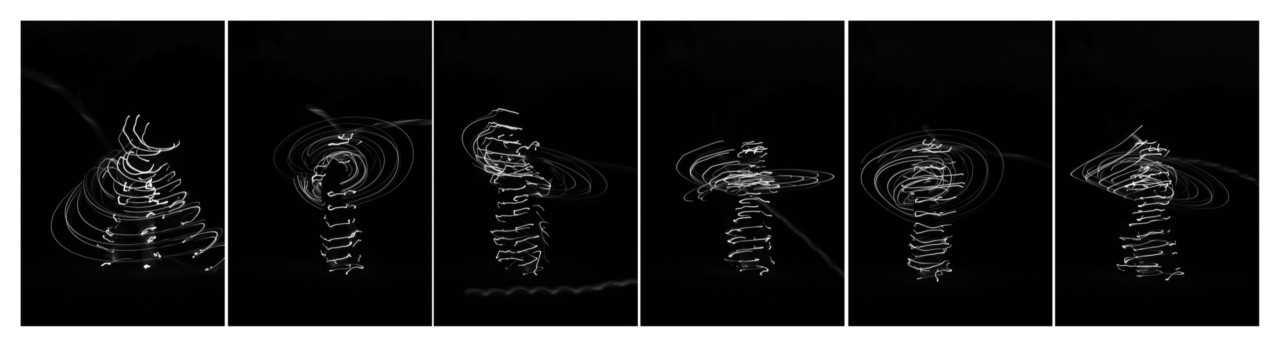

The visual language of the piece – all taking place in a back garden as common place to Australian culture as cricket itself – unwinds through a narrative that takes in a hazmat-suited figure rolling turf above, in which a spider waits, lacing the film with an unspecified looming threat. The rolled up turf is doused in fire and set alight. Jem and Dash are flanked by other batters, children their same age, who then one by one leave the picture, fading into a black expanse as they go. Balls fall through a vent of light through which some children catch the ball and others don’t. The culmination finds Jem and Dash, once so free, wired up mechanically as they perform, the viewer now so aware of their athletic inclinations that we still associate their action with their personalities – even as the image becomes a computerized, white on black other-worldliness. Eventually they are just a sequence of moving lights, accelerating and accelerating and repeating and repeating, until the switch goes off.

“The game of cricket can be such a force of contradictions,” Autio says, before reverting back to the deeply personal subjects which accommodate the universal. “For us, it was about using a piece of art to answer some concerns we were also having as parents.” Back to the questions then. “The answers are always around us”, Parke says, their children now older than he was when he first started asking the unanswerably big questions cricket soothed, “it just depends what questions we want to ask”.