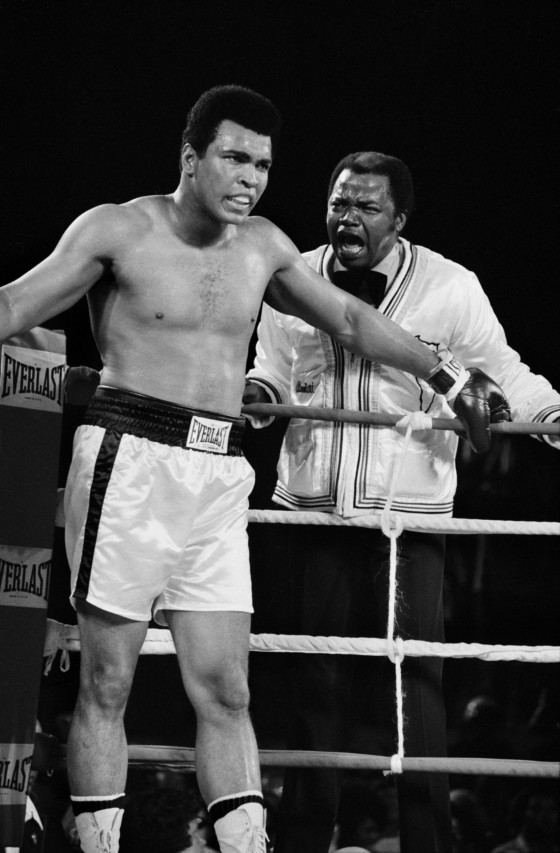

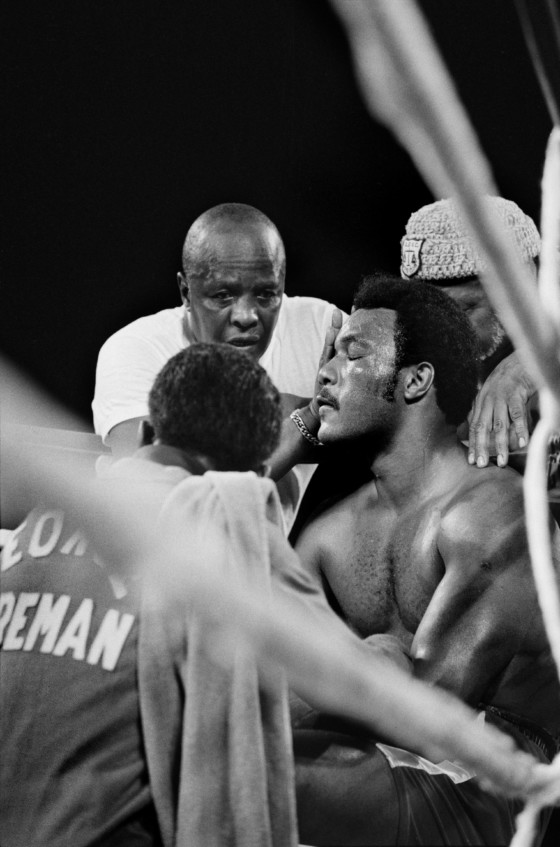

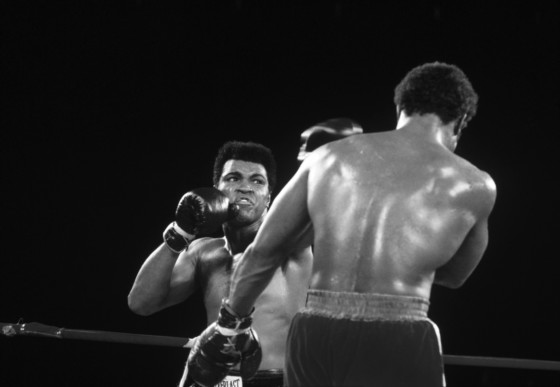

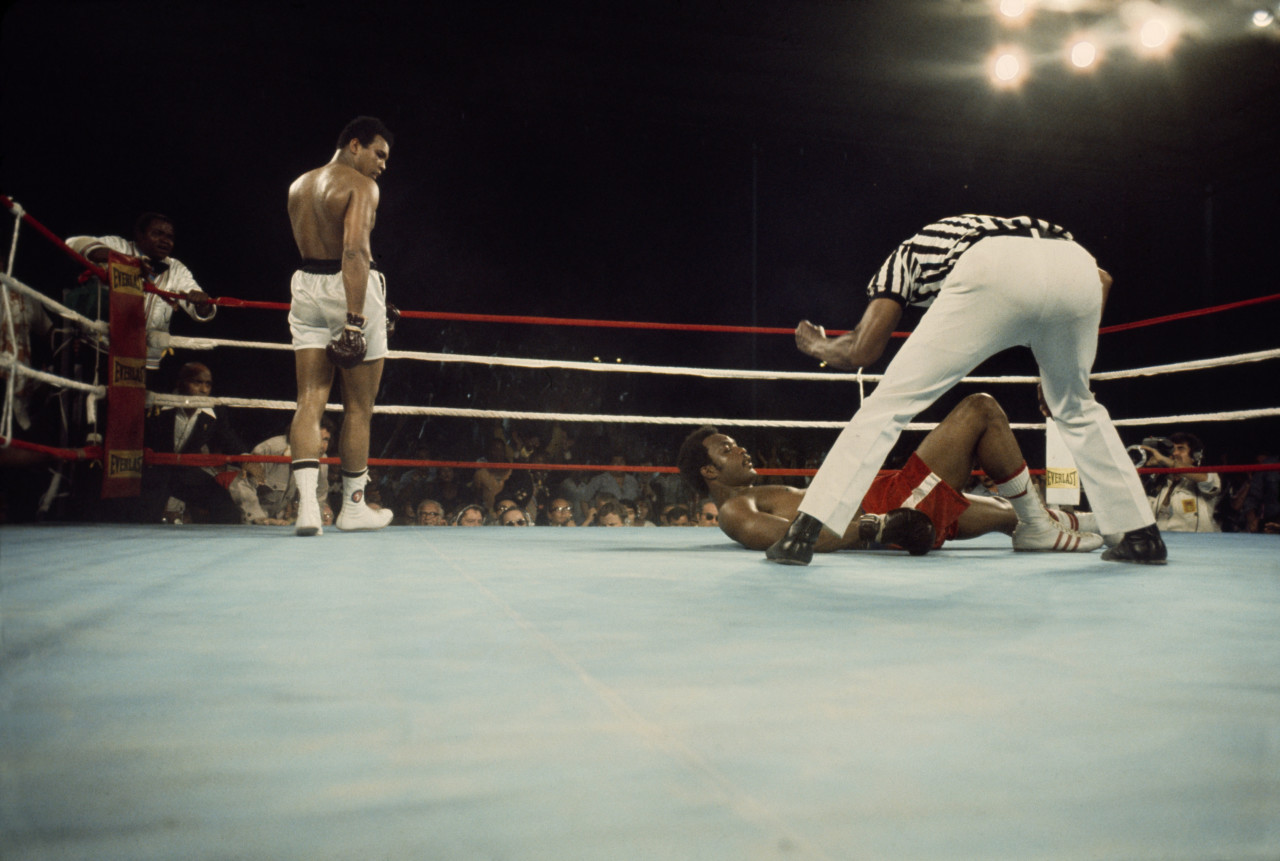

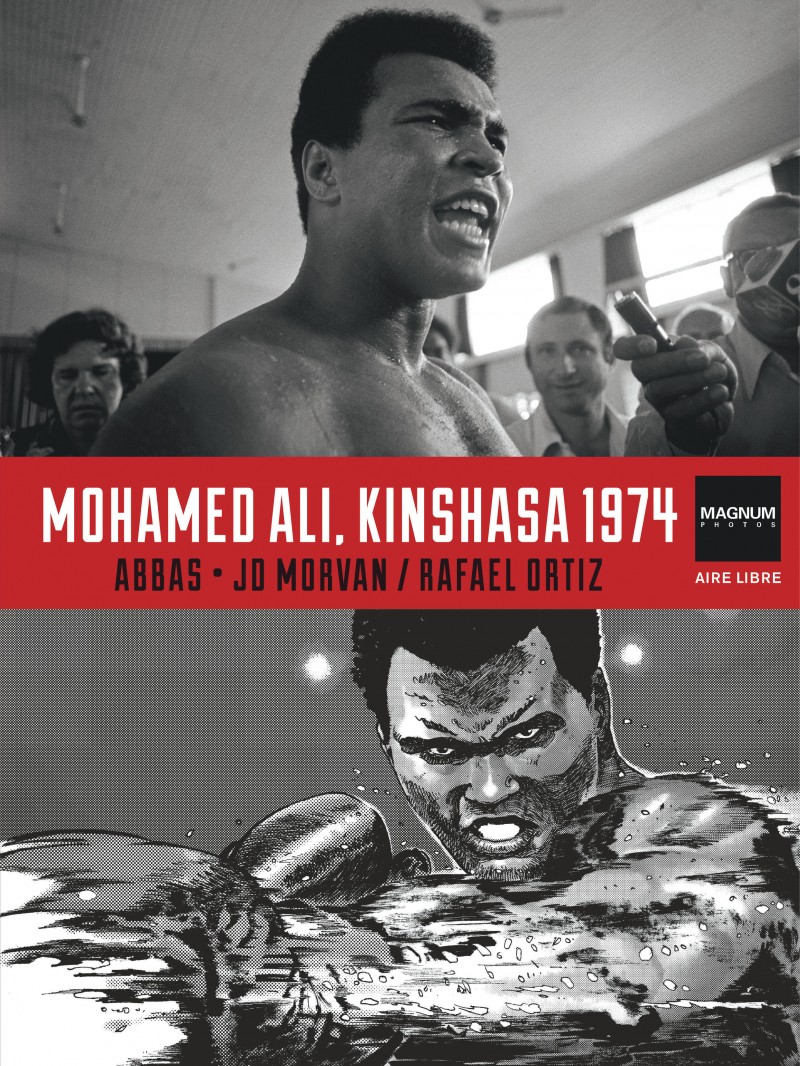

The boxing match known as the Rumble in the Jungle, fought between Muhammed Ali and George Foreman in 1974, was documented by Magnum photographer Abbas during the time he spent making work in Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ahead of the release of the new book, Mohamed Ali, Kinshasa 1974, by Dupuis, we reflect on the history of the event and speak to Hamish Crooks, Abbas’ son, manager of the photographer’s estate and former head of licensing at Magnum Photos, about boxing, Abbas’ photographic practice and the significance of photography in the construction of Ali’s legend.

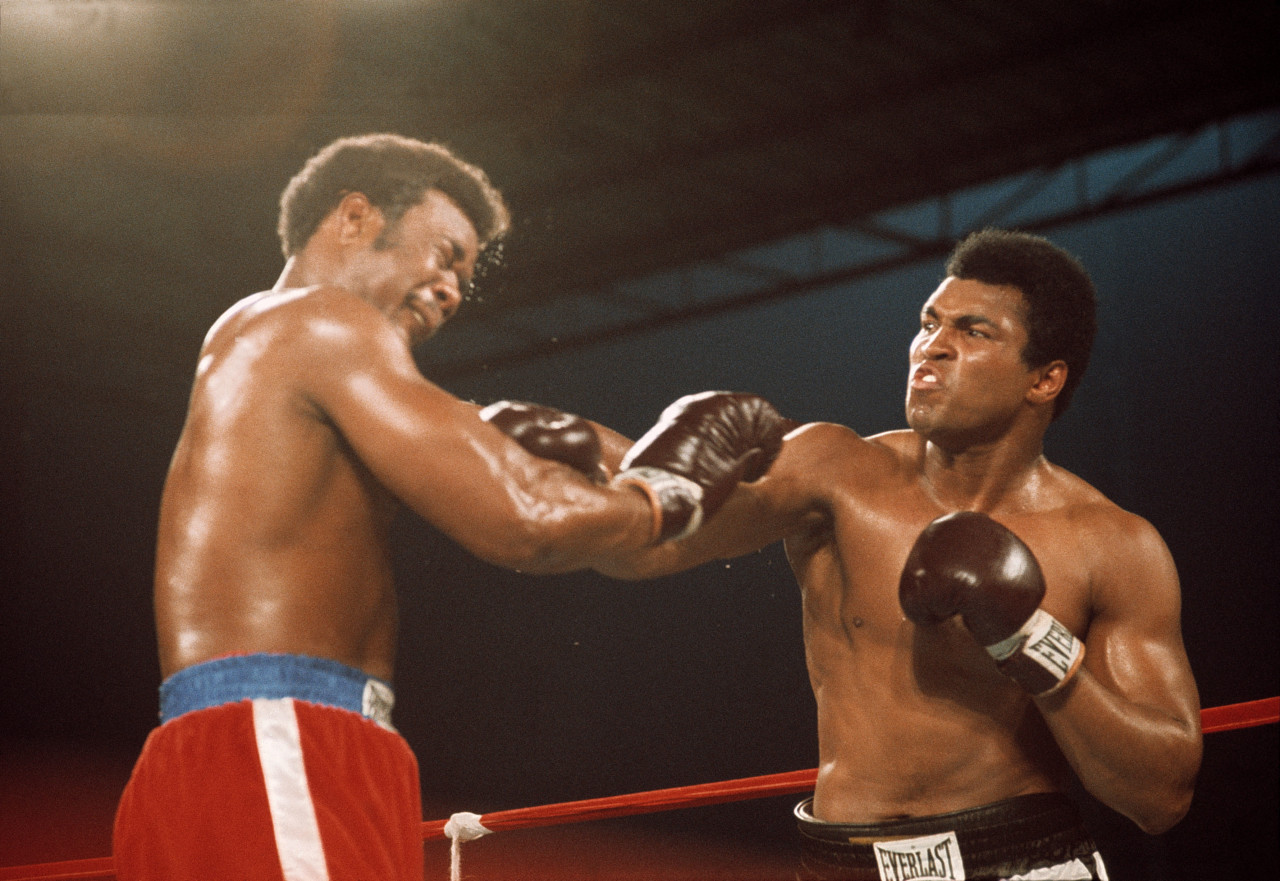

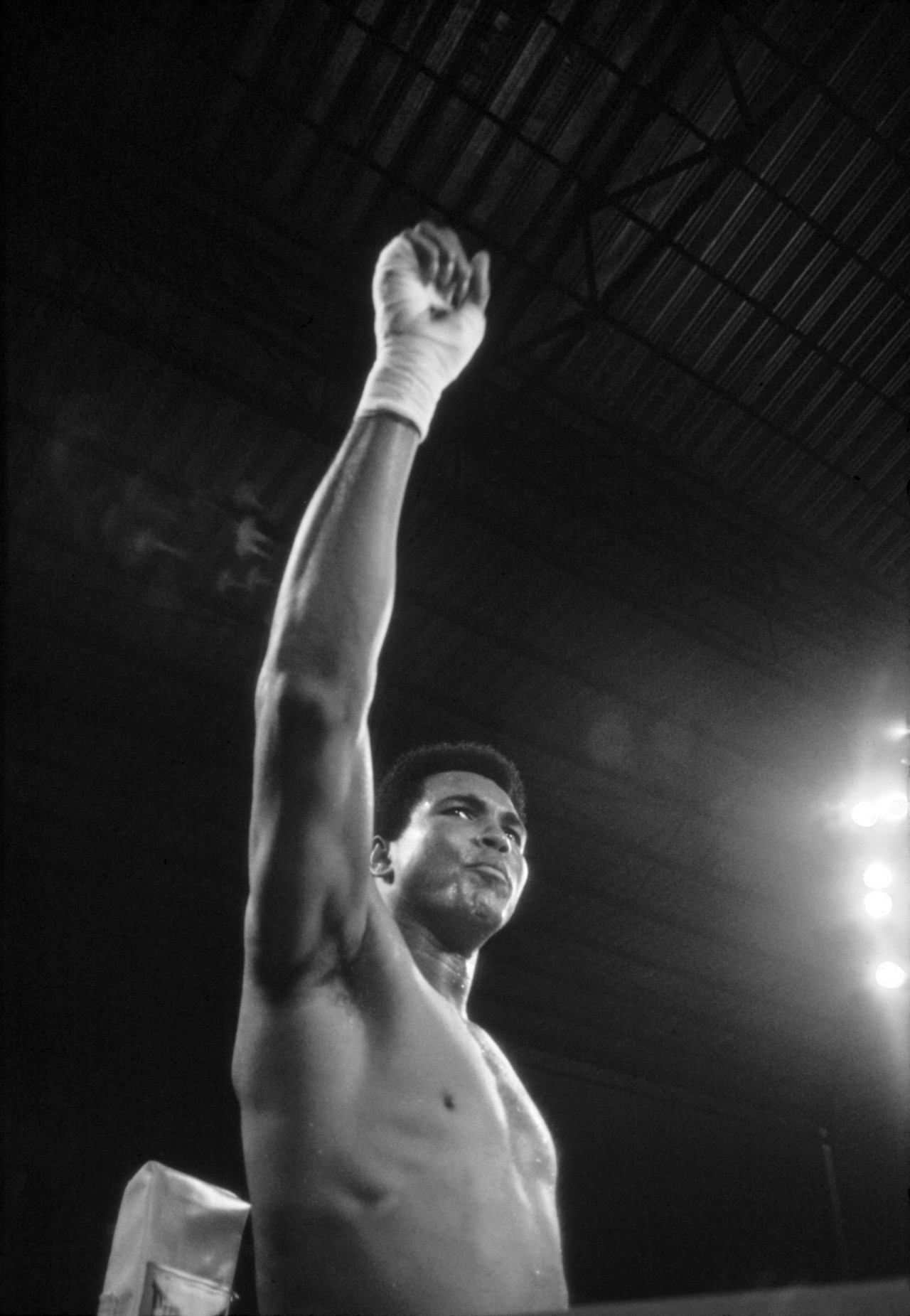

In the autumn of 1974, the world’s biggest sporting event was being in held in a new state in Africa. Zaire, formerly known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was to host a boxing match in its capital Kinshasa; a contest between Muhammad Ali, the former heavyweight champion of the world who was 32 — already into retirement age, and George Foreman, a younger fighter and reigning heavyweight champion whose unflagging power in the ring had led many to describe him as undefeatable. Ali had previously won the world title defeating Sonny Liston at age 22, but had been suspended from boxing following his refusal to be drafted into the Vietnam War; four years out of practice, odds were not in his favour.

Franco-Iranian photographer Abbas was working for the magazine Jeune Afrique, who had sent him on assignment to profile the nascent Zaire for their series of books on countries of Africa. Abbas had an enduring connection with Africa. He had lived in Algeria for fifteen years as a boy, and spent many of his later years living and working in West and Central Africa. Following the end of World War II and throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, old colonial powers – including France, Belgium and Britain among others – were losing imperial control of nations across Africa. These colonial powers were often replaced by neo-colonial influences, both of former rulers, and of the newer American and Soviet superpowers. Concurrently African nationalist movements were growing in power and popularity: it was a pivotal time for much of the continent, and provided fertile ground for photojournalists to make work.

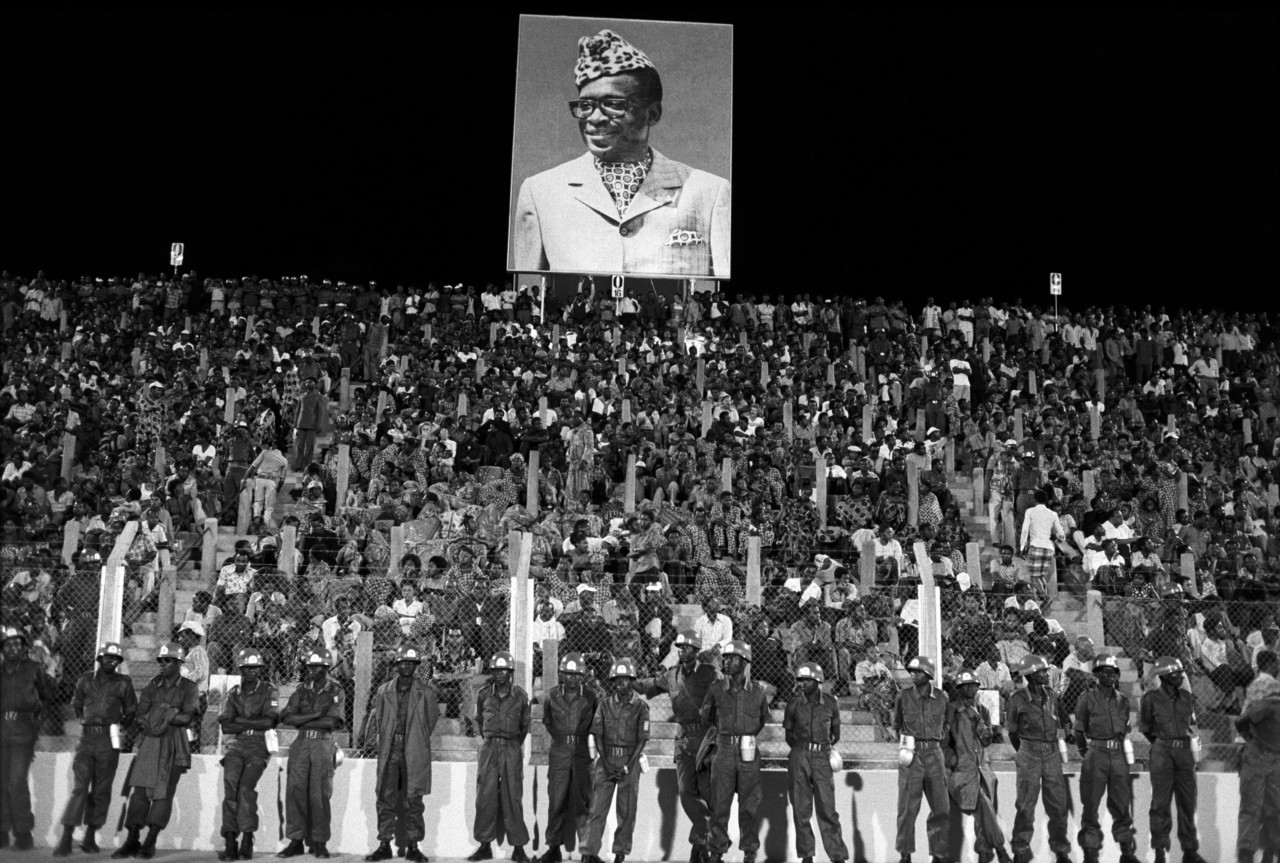

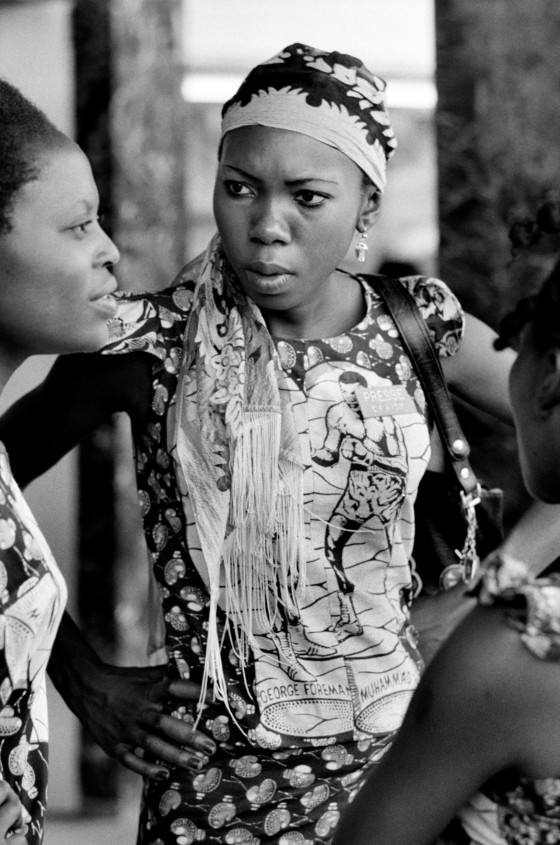

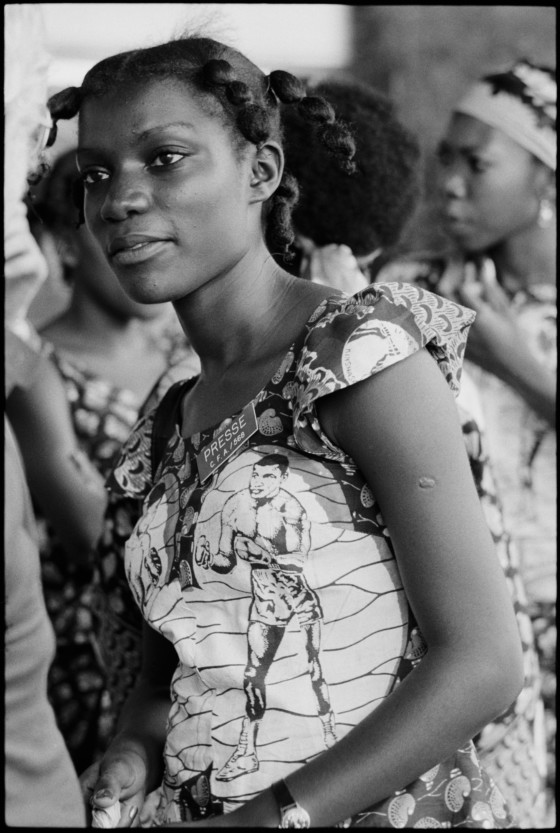

The Ali vs Foreman fight is sometimes thought of within a wider context of large-scale sporting events used as a distraction from problematic political environments – a practice commonly referred to today as sports-washing. Mobutu Sese Seko was under scrutiny for his actions during the Congo Crisis of 1960, the circumstances behind his succession to power, and the methods he used to consolidate his authoritarian regime in the country. In 1960 the military leader had removed the prime minister Patrice Lamumba and facilitated his execution by the Belgian-backed secessionist group, the Katanga. Lumumba had played a pivotal role in Congo’s separation from Belgian colonial powers, but his appeal for help from the Soviet Union was looked upon unfavourably by the United States, who had provided financial support to the Katanga. It is sometimes rumoured that the CIA played a role in setting up the Ali vs Foreman fight: so unusual were the circumstances in which it came together. Don King was at the time an inexperienced boxing promoter who took a major risk in proposing a $10-million-dollar purse for the fight, who had also managed to convince Mobutu that the event would put his country on the map. The fight was planned to capture international attention: the match itself was broadcast at 4am local time to coincide with prime viewing time in the United States, and a music festival was organized in Kinshasa to coincide with it, featuring popular artists such as James Brown, BB King, Miriam Makeba and Bill Withers.

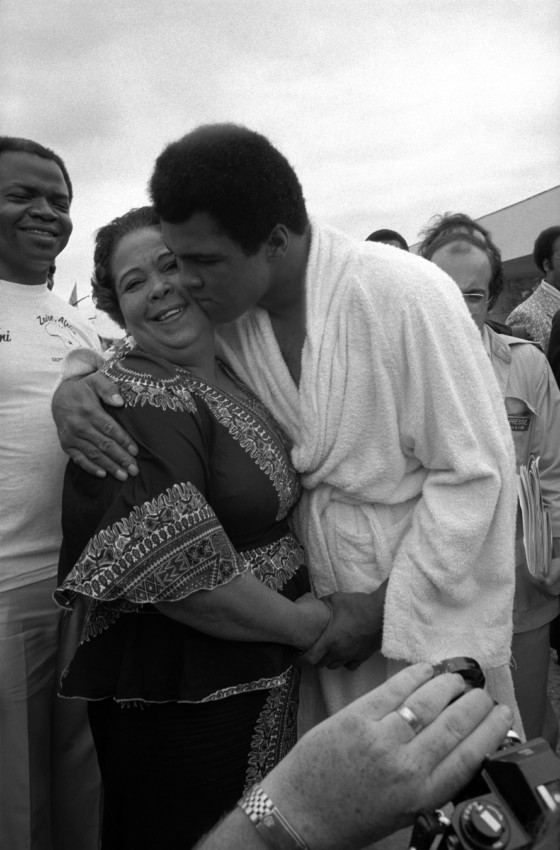

Mobutu himself wasn’t a fan of boxing and opted to watch the fight on closed-circuit TV, rather than putting himself at risk by attending the match. The dictator received Ali in his court before the fight. Abbas was present to document the event. Hamish Crooks, Abbas’s son, manager of the photographer’s estate and former head of licensing at Magnum Photos, has one of the images hanging on his wall at home. “Mobutu looks really vain. Ali looks determined, and Mobutu’s just like, ‘Look at me… all the Europeans are coming to photograph me.’ That was symbolically powerful at the time.”

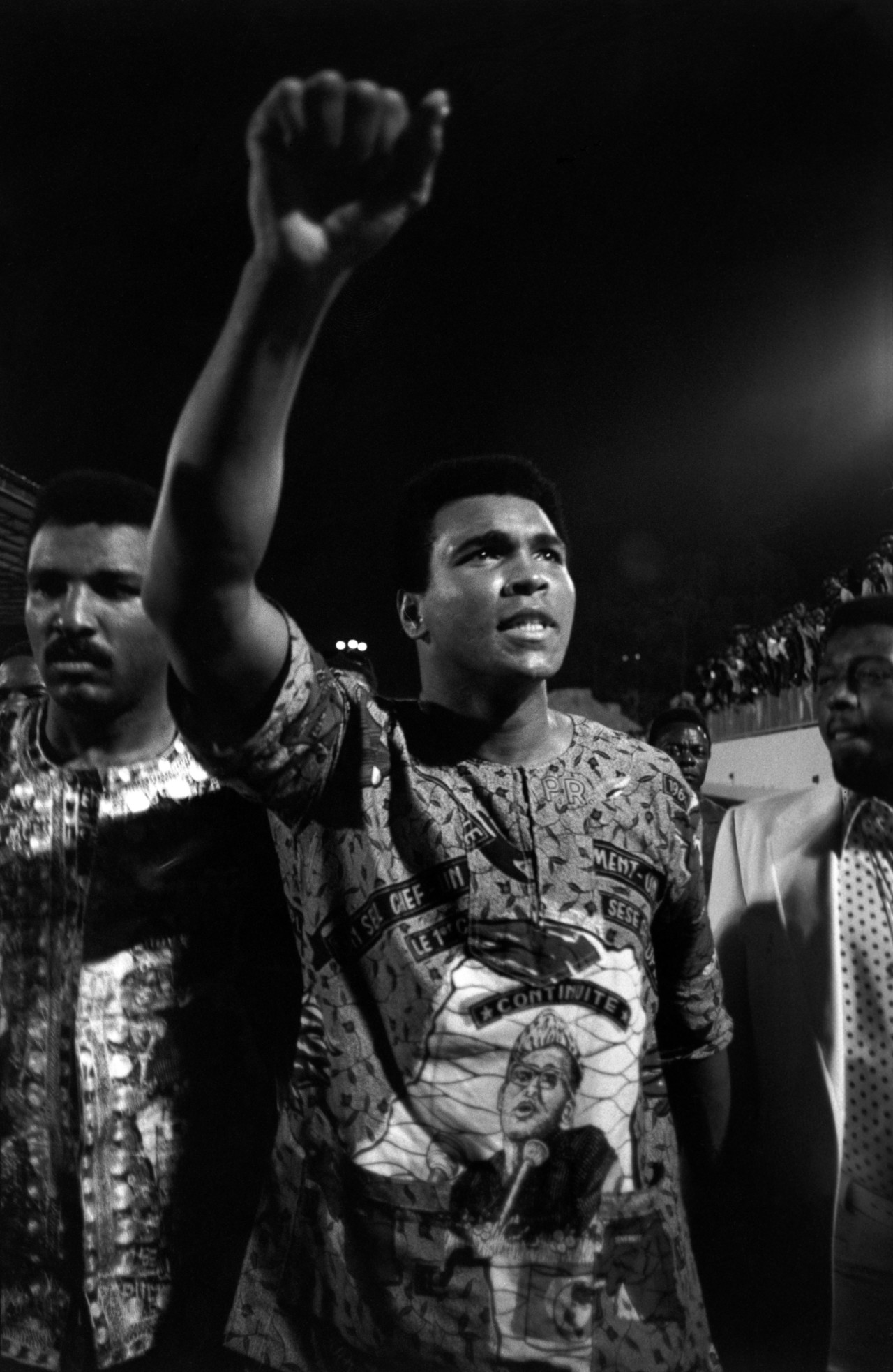

The undercurrent of racial dynamics in America, as well as burgeoning nationalism in regions of Africa, played a significant role in how the fight was perceived. In his notes, Abbas recalls Muhammed Ali “playing the anticolonialist card”, with George Foreman stepping into the role of “la Belge”, the Belgian. Foreman had unfortunately contributed to the comparison by bringing his dog, an Alsatian, to Zaire with him: a breed often used by Belgians in policing and the military. Ali himself played into this dynamic. A member of the Nation of Islam from 1961, and at that time a supporter of racial separatism in America, he often drew on his political beliefs while provoking his opponents. For example, Ali famously accused rival Joe Frazier of being an ‘Uncle Tom’, saying “he’s a brother, one day he might be like me, but for now he works for the enemy.”

Crooks, a boxing enthusiast himself, observes how the politics of the sport manifested in journalism and mainstream perceptions during that era. “George Foreman used to wave the American flag, so he was the total opposite to Ali. Ali himself knew no one would be interested in the fight, unless they started to make the divisions between the fighters. You needed some antagonism: ‘I’m fighting for black people, he’s not’. Marketing a fight with two black fighters before the 1970s was difficult as the largely white audience had less identification with two black fighters. Then Ali showed up as representing the radical black liberation political discourse of the time, which troubled many white Americans,” he says.

Ali’s rhetoric also attracted pro-black sympathies in the US, and provided the promoters with a great PR narrative. “His opponent would become ‘white for the night’ [as proclaimed by the media] in the hope they’d beat him.” Thus divisions between black identities in the US became a story of black versus white: “It added a level of identification for the fans to get behind.” Crooks stresses the multiple layers of interpretation that the symbolism of boxing titles is subject to, and the ways in which a culture invests in them as a result: “I always think it’s very important to remember how significant the ‘Heavyweight Champion of the World’ was viewed as being at the time. You are the ultimate male of the species in many people’s eyes. That’s why we have phrases such as ‘Great White Hope’ — the saying was first used when Jack Johnson, the first black man to win in the 1900s, won the title. The headlines in the newspapers talked of finding a white man who could beat this ‘uppity black man’”.

"Ali himself knew no one would be interested in the fight, unless they started to make the divisions between the fighters. You needed some antagonism: ‘I’m fighting for black people, he’s not’."

- Hamish Crooks

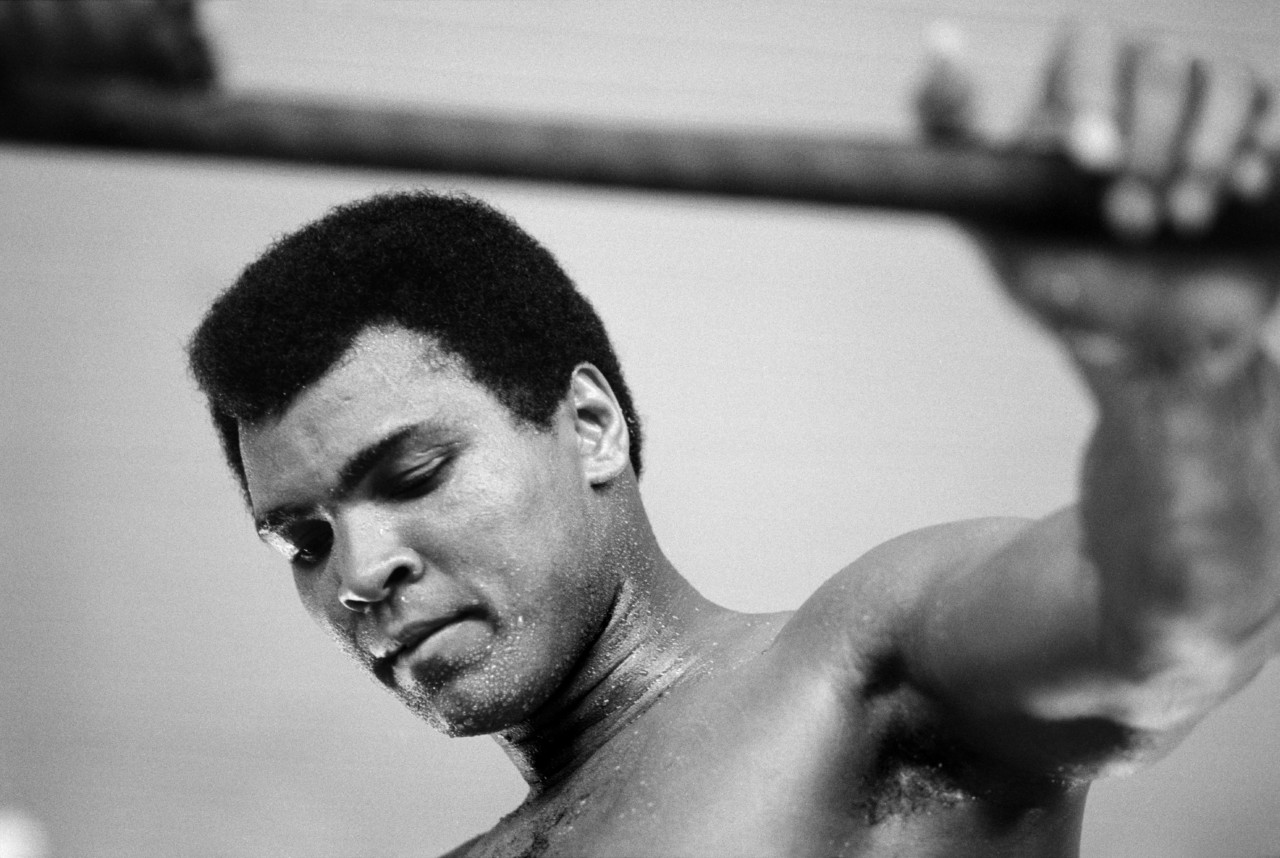

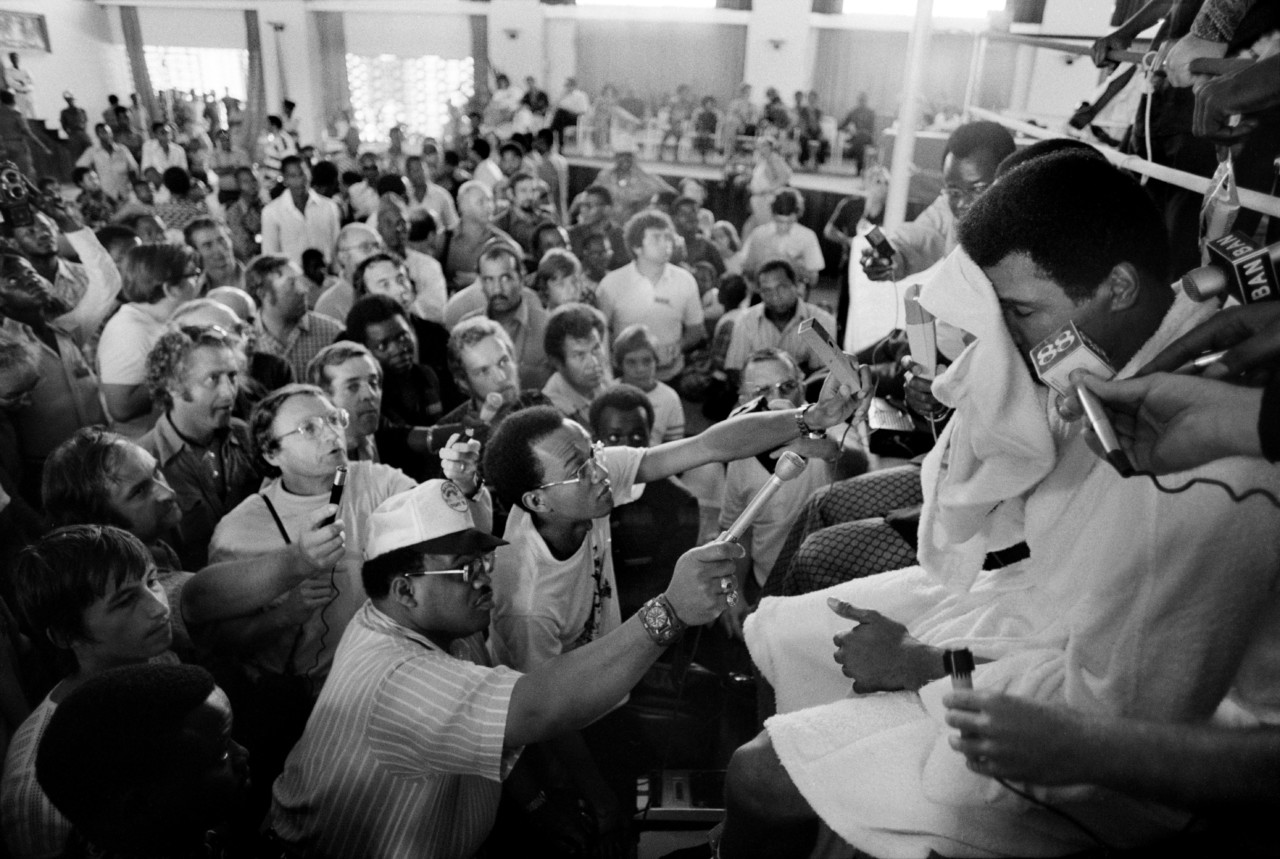

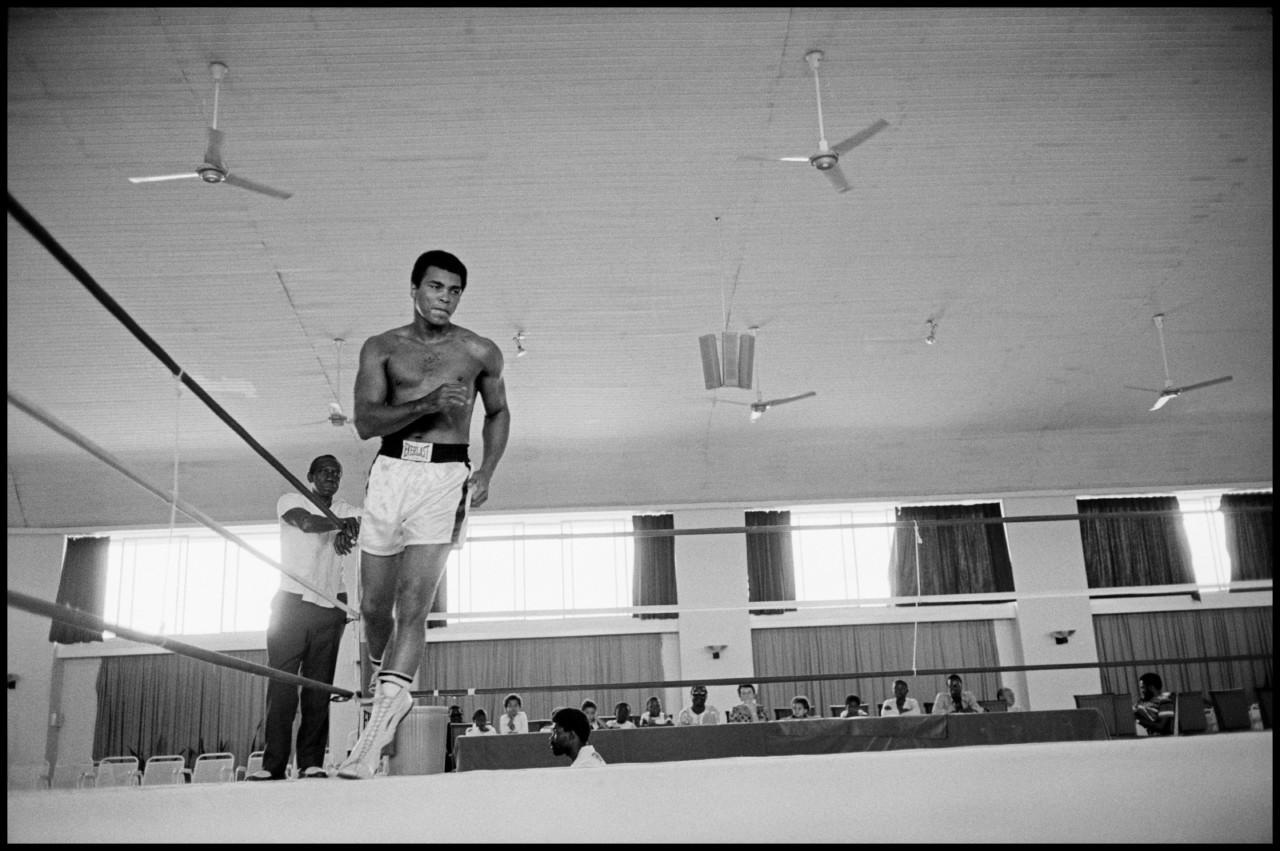

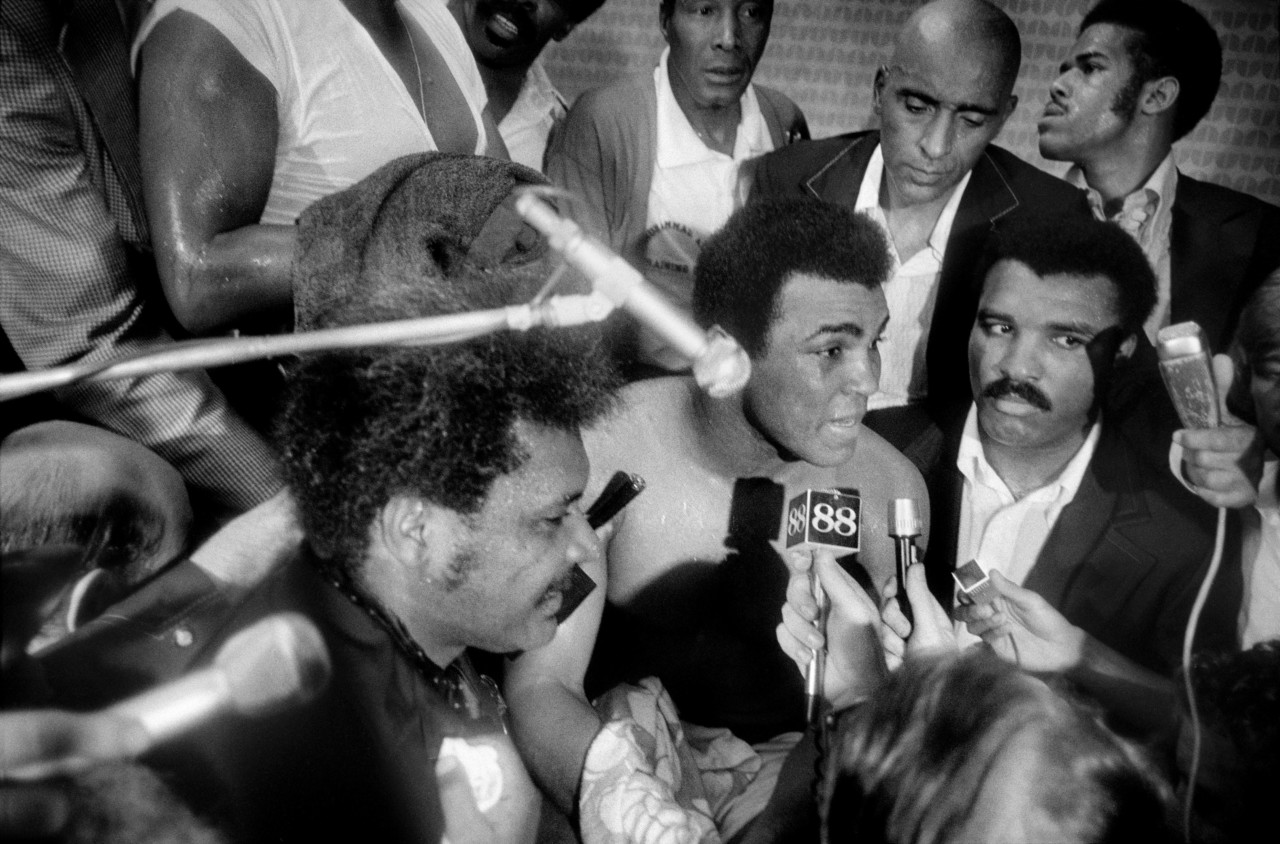

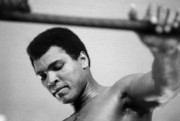

In a context where narratives played a crucial role in the impact, culturally and commercially, of huge sporting events, image makers were of course key. “Things like my old man [Abbas] coming in… what [some photographers] would have done was not just going to the fight. They’d be going to the training,” continues Crooks, “They’re storytellers, not photojournalists — photo essayists. Because Ali’s so big, they would’ve thought: ‘I need to see more than just the fight’. So you’d go to the training and the press conference, and backstage. Ali understood as well — he was thinking ‘Let them in. It’s good for the publicity’.”

The crafting of the story around Ali contributed to the elevation of the Kinshasa fight, and Ali’s public persona, beyond a sport-specific audience. It infiltrated cultural consciousnesses. “In the run up to fights you’d see all these pictures rather than waiting for press conferences. And that does add to the whole mystique, you’ve suddenly got this fighter you’re seeing in training… he’s not on the back page [in the sports section of the newspaper]. He’s in the front page. He’s in the magazines. And the news people do 10 pages on him, and those photo essays became important. He transcended the sport, so everyone become interested in looking at that.”

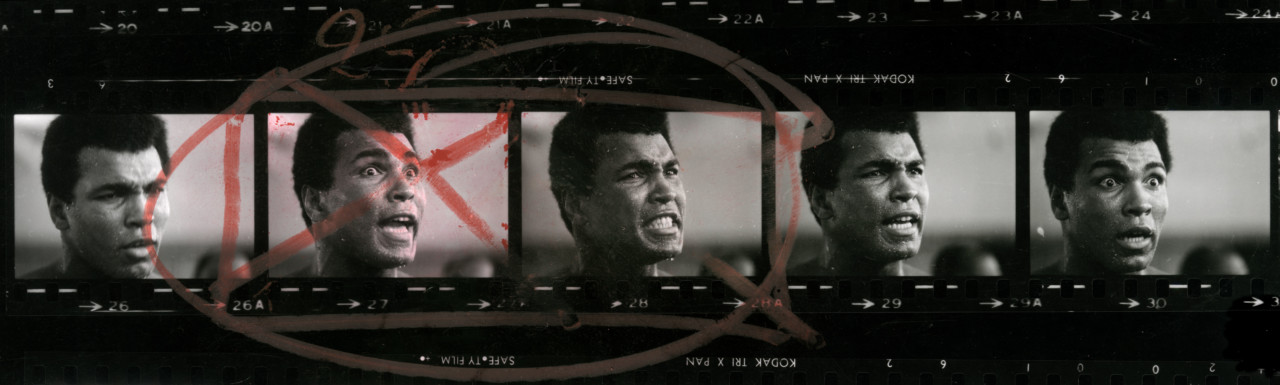

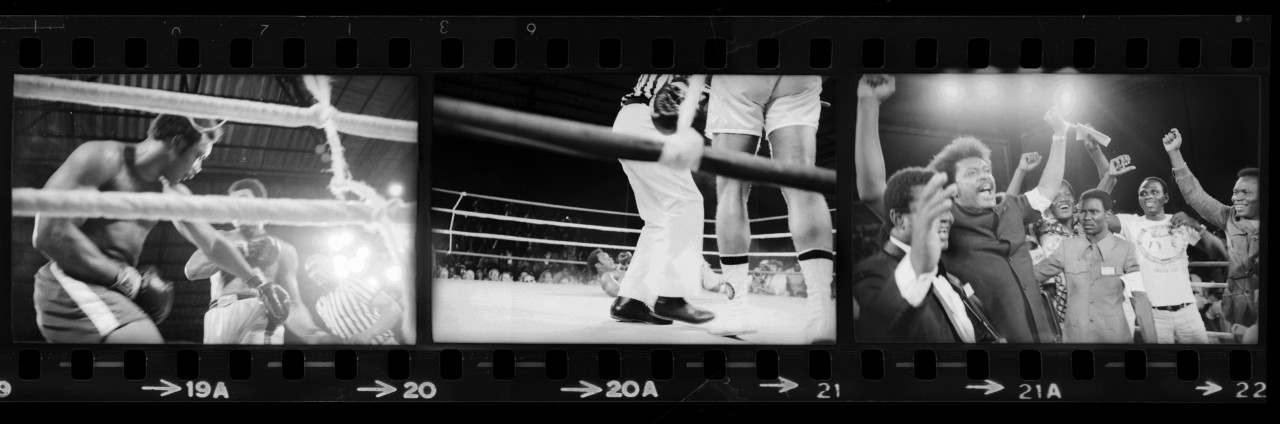

Crooks considers the retroactive appraisal of the photographs important to understanding the larger picture of events. It’s a unique and dual position he sees the images from, examining the photographic practice and world view of his father, as well as working with the images critically for commercial distribution in his former role at Magnum. “I’ve seen my dad, he goes to the contact sheet on a lot of things and the stuff that wasn’t chosen is very interesting now. Luckily he shot it because a lot of photographers didn’t,” he says. The set of images distributed to news outlets at the time—by Abbas’ former agency, Gamma— would have consisted of no more than 20 or 30 images. The photographs collected in his 2010 book, Le Combat, and in Magnum’s licensing database now —expanded to a series of 88— describe a longer-form story, revealing of Abbas’ photographic approach. “My old man shot in black and white, but he had to shoot some color for the front pages,” says Crooks. “There’s not much on the training camp in color. Only the fight. With the training, he’d say, ‘That’s my way of photographing. This is my story, I’m doing it in my way’.”

“When they did the editing at Magnum they’d go back and that’s what they’d be looking for, those things that the photographers didn’t originally edit. My dad’s Vietnam book included a great portion of the bits that no one wanted to see at the time. [The news outlets of the day] just wanted the bangers, but that book revealed a wider picture. That included formerly unseen images of Vietnamese society and the effects of war that have become more interesting now. It’s a similar thing with Ali. You want to see a bit more, you want to go in and see how he eats, how he trains, what’s he like. You used to call it a ‘color’ story in journalism.”

Crooks doesn’t see Abbas’ photographs on their own as having played a particularly significant role in public perception of Ali. “Muhammad Ali’s the most famous man in the world. There were hundreds of photographers there,” he says, “The thing that you’ll find that makes things different is access to the pictures. Magnum has a library and it’s accessible. Our pictures have probably been used more than a lot of others. But there’s a lot of good pictures out there that are in libraries that are not as readily known or accessible as Magnum’s.”

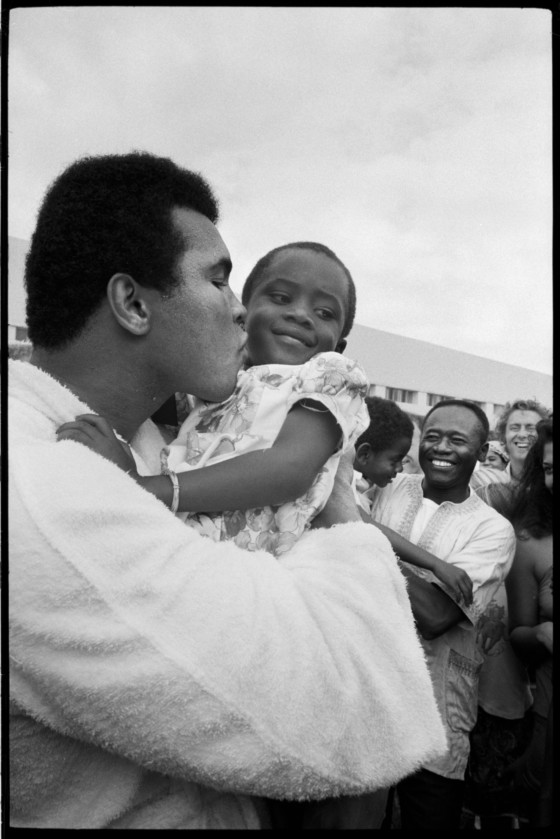

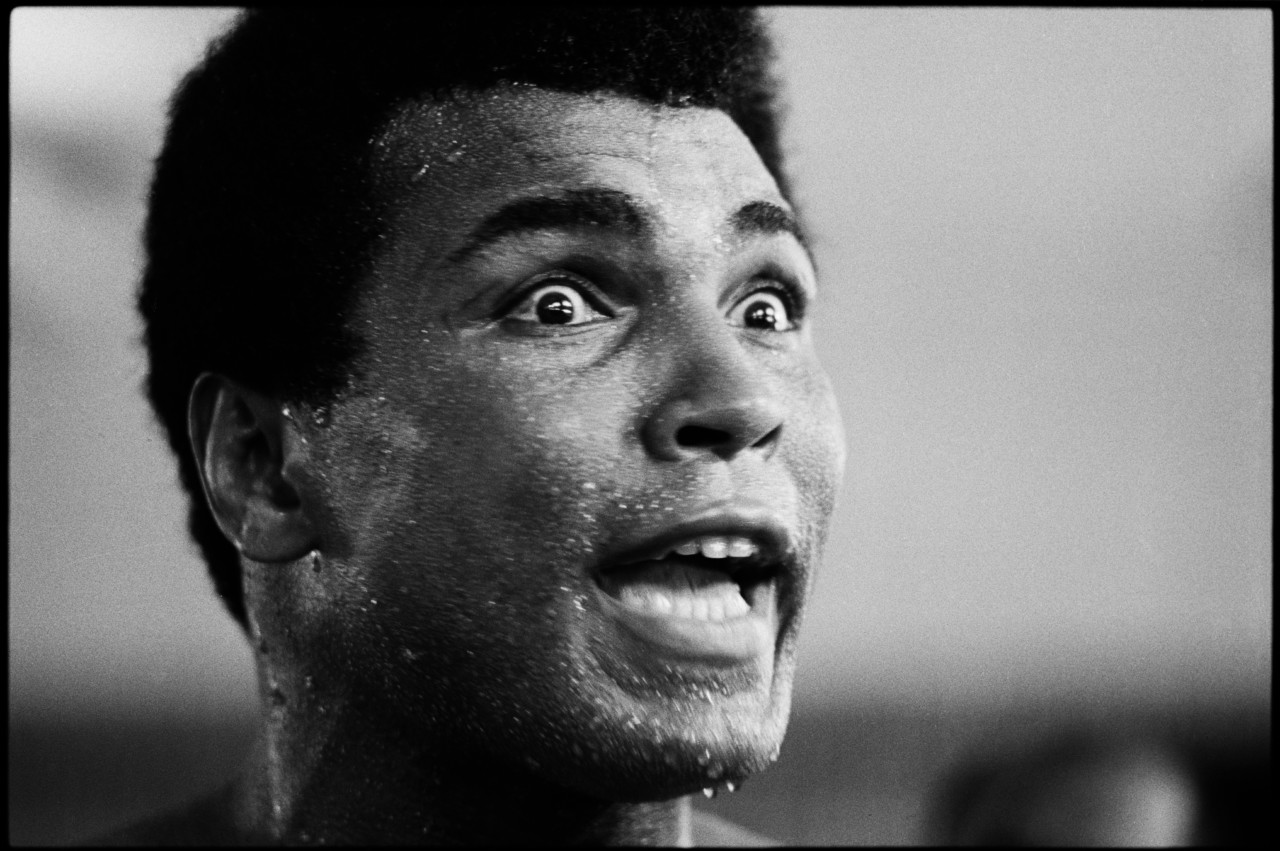

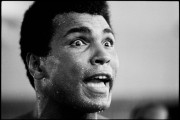

“My old man became quite well-known but I don’t think those pictures added anything to Ali’s legacy,” Crooks continues. “The Rumble in the Jungle pictures… and even Thomas Hoepker’s pictures… Ali’s Ali. As my old man said, he was such a brilliant person to photograph because he knows. He’s always on. He said he was fantastic to be around. He was like a journalist’s dream. And just physically, he said there was just this aura. This is a guy who could barely read.” The boxer, who was frequently the center of attention in any room, was also severely dyslexic. “[My father] said you were just sitting there going, ‘this guy’s sharper than all the journalists in here’.”

We ask Crooks whether he has any further insight to share about the time the photographer spent in Kinshasa with the Champ. He’s still waiting for his chance to pore over Abbas’ notes in depth. “We’re not allowed to read his diaries for five years [after his death],” he says, “Though I we can’t fucking read them anyway because the writing’s illegible. It’s totally tiny, minute — it’s unreadable, and it’s in four languages.” He does remember a few further insights his late father shared. Ali was a playful and effervescent character in public, but always had a dangerous edge. “My dad said you could see it in his eyes all the time — even when he saw him a few years later when he’d got Parkinson’s, it was still those eyes. That guy’s tough, he said, you could see steel.”

The graphic novel featuring Abbas’ photographs of the Rumble in the Jungle, Mohamed Ali, Kinshasa 1974, is available from Depuis from June 5, on their website.